An Assessment of Current Quality Assurance Practices and Ongoing Work to Develop a Comprehensive Quality Plan for U.S. Census Bureau Business Register

An Assessment of Current Quality Assurance Practices and Ongoing Work to

Develop a Comprehensive Quality Plan for U.S. Census Bureau Business Register

Eddie J. Salyers

U.S. Census Bureau

1. Introduction

This paper describes the ongoing work at the U.S.Census Bureau to maintain, measure, and improve the quality of its business register (BR) while implementing a major database redesign. First background on the BR is provided. Then current quality assurance practices associated with administrative records processing, direct data collection, and the interactive processes that support these activities are examined. In addition the activities of a team chartered to develop a comprehensive plan that ensures the continuous quality, reliability, and integrity of all business register processes, information and products will be reviewed.

In the fall of 2002 initialization of the U.S. Census Bureau’s new business register was completed. This was a complete database and software redesign that involved migrating data from the old VAX RDB® database system to an Oracle® database. As part of the redesign all the software to load and update administrative and survey data, and all the interactive routines were rewritten. In order to assure quality of the new BR is at a minimum commensurate with the old Standard Statistical Establishment List (SSEL), which it replaced, and to establish a complete quality framework, a quality assurance team was formed in 2004. This team consist of survey statisticians who maintain, use, and analyze the register in their daily work; mathematical statisticians who rely on the register to select samples; and mathematical statisticians with responsibility for the edits and quality assurance of the BR; and software engineers.

The team adopted the following definitions to guide their work:

Quality - "The totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bare on its ability to satisfy specified or implied needs." (ISO, 1986)

Reliability - “The ability of a system or component to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period of time.” [IEEE 90]

Integrity - Information in the system follows designated standards and is consistent both within an individual table as well as between associated tables.

2. Business Register Overview

2.1 Primary Functions

The primary functions of the BR are

Ø Source of frames for Economic Surveys

Ø A central repository for administrative records information (mostly Federal tax data), used throughout the Census Bureau's economic programs.

Ø A central support facility for collection and processing.

Ø The source of basic employment and payroll measures summarized by industry and geographic area in the annual County Business Patterns and ZIP Business Patterns statistical series.

Ø A research resource

Ø A ready-made data source for custom tabulations and other special studies (reimbursable projects)

Ø The basis for longitudinal studies that track units through reorganizations or changes in ownership and provide information on business demographics.

2.2 Scope

The scope of the BR is all legal entities (generally businesses) that operate within the U.S. and it’s island areas as identified by the Master File systems of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (taxing authority) except employers classified as private households.

2.3 Software

The BR is and Oracle database containing many related tables. An interactive web-based interface was built with Oracle Forms and PL/SQL for purposes of research and to update records. Many interactive and batch software routines are used to load, update, correct and edit data.

2.4 Statistical Unit Definitions

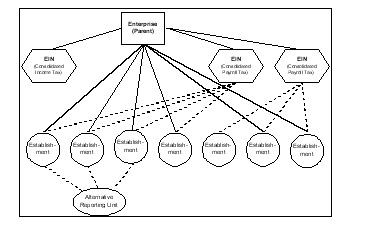

The Business Register identifies four basic types of statistical units, defined as follows:

Ø Establishment - An establishment is an economic unit, generally at a single physical location, where business is conducted or where services or industrial operations are performed

Ø EIN Entity - An EIN (Employer Identification Number) entity is an administrative unit that the IRS has assigned a unique identifier for use in tax reporting

Ø Enterprise - An enterprise is an economic unit comprising one or more establishments under common ownership or control.

Ø Alternative Reporting Unit – Units established by the Census Bureau specifically for data collection for industries that cannot report establishment data. These units typically represent a part of the company made up of all activity within a given industry and geographic area

There is great variation in the complexity of business organizations. A most basic and useful distinction along the complexity dimension is one between single- and multi-establishment enterprises. For single establishment companies the enterprise, establishment, and EIN units are the same.

The relationships among larger companies can be very complex involving tens of thousands of establishments and thousands of EIN units. Figure 1. shows an example of the relationships among these units for small enterprise.

Figure 1. Example of Statistical Unit Relations for a Small Multiple Establishment Company

Accurately identifying and maintaining the links among these components of an enterprise is a critical component of the quality of the BR.

2.5 Data Sources

The BR integrates information from several sources to achieve a practical and effective balance among competing demands for comprehensive coverage, diverse and accurate content, timely updates, low cost, and minimal response burden. The data sources and their respective roles in BR construction and maintenance are described below:

2.5.1 Administrative Records

Administrative records are the foundation of the BR. They provide indispensable information that is low in cost, timely, comprehensive, and generally quite accurate. Further, administrative records allow the Census Bureau to satisfy much of the BR’s substantial data requirement while imposing minimal response burden. The BR’s principal administrative records suppliers are as follows:

n Internal Revenue Service (IRS) – The IRS is the largest provider of administrative data for the BR. The BR obtains information about business and organizational taxpayers from the following specific IRS sources:

ü Business Master File Entity/Directory (BMF) – The BMF identifies EIN entities representing all business, organizational, and agricultural taxpayers known to the IRS. Content of these BMF extracts includes EIN, proprietor’s Social Security Number (SSN), if applicable, and other identifying information; legal and trade names; mailing and physical location addresses; principal business activity (industrial) classification; and selected control, status, and processing indicators. BMF information is critical to the BR, particularly for identifying newly established EIN entities that represent business births.

ü Payroll Tax Returns - Business and organizational employers file the Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return, IRS Form 941 series, which is of primary importance; agricultural employers file the Employer’s Annual Tax Return for Agricultural Employees, Form 943 series. The Census Bureau receives weekly files from current IRS processing of both forms. Both types of return identify taxpayers by EIN, provide total employment for the pay period including March 12, and indicate the tax period covered. Additionally, Form 941 provides data by quarter and Form 943 by calendar year for wages.

ü Business Income Tax Returns- Annual business income tax returns provide basic measures of business receipts or revenue and assets; most returns also provide a principal business activity (industrial) classification. The Census Bureau receives weekly files from February through December, which contain data from current IRS processing.

n Social Security Administration (SSA)—New business and organizational taxpayers (i.e., births) file an Application for Employer Identification Number, Form SS-4, with the IRS. Form SS-4 content supplied to the Census Bureau includes EIN, Industry (NAICS) codes, geographic information, estimated employment, and other classification/status indicators. The Census Bureau receives monthly files from current SSA processing, which lags Form SS-4 filing by some 8-12 months.

n Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)—The BLS maintains a separate business register, known as the Business Establishment List (BEL), based on information collected in connection with unemployment insurance administration. Each quarter, the Census Bureau prepares a file of EINs that identify unclassified single units and partially classified manufacturing single units from the SSEL. The BLS refers each of these EINs to their BEL and returns the corresponding NAICS code whenever one is found.

Table 1. Economic Administrative Record Files: Frequency and Record Count

Total Number of Records Annually BMF Annual Annual 24 million BMF supplements Monthly 18 million 941/943 Weekly 23 million 1040 Business Income Tax Returns Weekly 20 million 1120/1065/990 Business Income Tax Returns Weekly 8 million SSA Business Births (IRS Form SS-4) Monthly 1.8 million BLS industry codes Quarterly 1.2 million 851 Business Income Tax Returns Bi-annual 0.5 million

Item

Frequency

2.5.2 Census Bureau Collections

The Census Bureau also updates the BR based on direct data collections in the Company Organization Survey (COS), Economic Census, and current surveys.

Ø Company Organization Survey (COS)—The COS is a register proving survey or profiling survey, done specifically for the purpose of maintaining BR information about the establishment composition, organizational structure, and operating characteristics of multi-establishment enterprises. A separate collection for this purpose is necessary because administrative records do not delineate the relationships among multiunit enterprises, their EIN entities, and their establishments, as the BR requires. The Census Bureau conducts the COS annually. This annual survey panel is drawn from the BR population. The procedure for constructing this panel selectively targets enterprises that are most likely to report changes in establishment composition, organizational structure, and/or operating characteristics, based on enterprise size and complexity and on administrative records indications (determined by applying selection rules to associated EIN entities). Additionally, the panel includes a small probability sample of enterprises not selected by the targeting procedure. Enterprises included in each year’s panel account for approximately 80 percent of multiunit employment and payroll.

Ø The instrument includes inquiries on ownership or control by a domestic parent, ownership or control by a foreign parent, and ownership of foreign affiliates. Further, the instrument lists an inventory of establishments belonging to the enterprise and its subsidiaries, and it requests updates to the inventory, including additions, deletions, and changes to information on each establishment’s EIN, name and address, and industrial classification. Finally, it collects each establishment’s end-of-year operating status, employment for the pay period including March 12, first quarter payroll, and annual payroll. These COS inquiries, combined with economic census inquiries during years covered by the census, are the primary source of the information that the BR records for multiunit establishments

Ø Economic Censuses—The economic census, done at 5-year intervals (covering years ending in ‘2’ and ‘7’), is a comprehensive enumeration of the United States business population and, therefore, a valuable source of information for SSEL maintenance. Of particular importance are identification of new multiunits and other coverage improvements resulting from systematic analysis of census data, updated address information, and more accurate industrial classifications based on detailed census collections for value of product and/or service outputs by category and other classification factors. Economic census and COS programs are closely integrated , ensuring timely BR updates based on results of these collections.

Ø Current Economic Surveys—Although administrative records, the COS, and the economic censuses provide the great majority of the information needed to maintain the BR, the Census Bureau’s monthly, quarterly, and annual surveys are important sources of additional updates. For example, the Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) is closely integrated with the COS and provides valuable feedback of coverage and classification information for manufacturing enterprises and their establishments. Similarly, the monthly economic surveys are often the first to identify new multiunit establishments, changes in ownership, and updated address information, and they feed that information back to the BR.

3. BR Quality Assurance

3.1 Migration from old SSEL to new BR

The new BR was designed to both improve support for business surveys and to strengthen its effectiveness in providing comprehensive and accurate coverage of the business populations those surveys cover. In order to achieve these goals and provide a database that could store all the relevant source data; provide a flexible design to accommodate new data availability and requirements; provide flexibility to fully support the statistical units described above; and allow for new types of units, the new BR design is radically different from the old SSEL. One major change was the creations of new identification numbers (ID) for register entities. The SSEL identified entities by EINs and Census File Numbers. For single establishment companies the Census File Number (CFN) was ten digits consisting of “0” + the EIN as assigned by IRS. Establishments of Multi-establishment companies were also assigned a ten digit number with the first six-digits number identifying the company and the last 4 being a location number. In the new BR it was decided to user a ten-digit serial number that has no embedded meaning for each register entity. This offers the advantage of allowing an establishment to maintain the same number irrespective of company organization changes or changes in their tax filing. The second major change was the creation of a centralized “Links” table that would relate these register entities to each other.

As noted in the introduction, in fall of 2002 the process of initializing the “new” BR was completed. Given the very different design this was not a simple copy operation, but involved considerable reformatting. Each program that reformatted and loaded data to the BR was thoroughly tested by a team of analysts and software engineers. While data were being migrated, administrative record data continued to “pour in”. Thus the final step of migration was to “catch up” on loading administrative record data to the BR. Once the loads were complete and the old SSEL and new BR were in a condition so they should now represent the same entities, the next step of quality assurance was to see if the migration was done accurately.

To ensure data on the old SSEL was migrated correctly to the new Business Register, a comparison of the 2001 SSEL and the 2001 Business Register was conducted. A one-to-one record match was made between the 2001 SSEL and the 2001 Business Register. Several differences caused by design such as not migrating inactive records had to be accounted for when reviewing the results. After accounting for these differences, the study found that there were no significant problems in the migration. Differences found between the SSEL and BR in this comparison were expected and due to the planned design of the new Business Register.

At a macro level a comparison of establishment counts, employment, and payroll of 2001 data from the old SSEL to the 2002 BR was performed to see if the changes at summary levels were within the expected range based on historic year to year changes. This comparison further checks the migration and provides some assurance that updates being made to the new BR since migration are in line with expectations. This comparison found that after accounting for definitional differences the values were consistent with expectations. Even though the load and edit programs were thoroughly tested prior to production given the complexity of the system untested scenarios are likely to exist after testing is completed. This comparison of the old 2001 SSEL to the new 2002 BR was an important measure taken to insure that implementation of the new BR has not led to a deterioration of data quality caused by errors or omissions in the new software.

3.2 Administrative Records

3.2.1 Current Quality Assurance Process for Administrative Records

Quality assurance for the BR’s administrative records inputs is a two-stage process. The first stage evaluates aggregate data in order to identify global errors that may warrant rejection of a whole file. Specifically, it tabulates distributions of the file’s variables, for example, count of tax returns by industry or by receipts size, and compares those distributions to standards based on levels and trends from three previous years’ data. If the comparisons identify items that fail to meet quality standards, the administrative records staff investigates those discrepancies and resolves them, usually by obtaining a corrected file or a reasonable explanation of the data from the source agency. Since the administrative records files were not directly affected by the development of a new BR, this first stage was not changed with the implementation of the new register.

The second stage uses record-by-record edits to identify reporting or processing errors that may affect individual tax reporting units (EINs) and individual variables recorded for them. These edits are generally of two types:

Ø Basic validity tests: These are elementary edits done primarily to ensure that each item has a legitimate form and, therefore, meets minimal requirements for data processing and storage—i.e., that a particular value is suited for the operations and storage location for which it is intended. Basic validity tests generally include examination of data type/format (Is the value a number, character string, date/time, etc.?), length, and value domain. For coded items, the tests usually include a “list of values” check as well.

Ø Ratio edits: These edits examine the consistency of correlated quantitative data by computing the ratio of two values and comparing the result to bounds (tolerance limits), which usually are derived from observed data distributions. The comparisons generally examine the same item from different (usually adjacent) reference periods, related items from the same reference period, or some combination of these alternatives. Ratios falling outside the bounds are indications of possible error(s), and the pattern of those ratio edit failures may localize the error(s) to one or more of the tested items.

When a probable error is found, the editing process will not allow a BR update for the suspect variable; instead, it lists the input record for review. The administrative records staff monitors resulting error listings and notifies the source agency if systematic errors are found. Later, BR imputation procedures supply estimates for items that are blank because administrative data edits would not allow an update based on a suspect value (probable processing or reporting error). The objectives and test included in these edits were largely unchanged with implementation of the new BR.

3.2.2 Analysis of Strengths, Weaknesses and Recommendations for Administrative Records Quality Assurance

The team formed to review quality assurance procedures has completed its initial review of administrative records processing and identified our strengths, weaknesses, and made recommendations for improvements. Although they identified several weaknesses in the current system, they found no evidence of a change in quality between the administrative records processing in the old SSEL and the new BR. This is in large part because, as noted above, the quality assurance practices for the incoming records were unchanged. The programs that load and edit administrative data that were rewritten appear to be working as expected.

n Strengths

l Identifies systematic file errors - Based on a review of the procedures in place to review incoming administrative records files and an assessment of how the system performed in the past, it was concluded that the current system does an excellent job of identifying global or systematic areas with the files. In the past problems have been identified that were a result of processing areas at the source agencies.

l Staff - The roles for processing and performing quality assurance on administrative records are clearly defined and the staff is experienced.

l Low Cost

n Weaknesses

l Lack of Macro-Level Post Processing Quality Assurance – While the quality of incoming records (inputs) is closely monitored; there are no systematic timely reviews of the results (outputs) or affect on the BR. Currently, a macro review of the BR is done as part of the County Business Patterns program that publishes summary data based on the BR. This review identifies and corrects large errors on an annual basis.

l Communication - The processing status of administrative records and the QA reports are not readily accessible online or routinely distributed to managers and users.

l Identifying significant problems with large cases -The current QA reports are based on checking that the numbers of administrative records in a file with specific values such as industry codes and employment size are within expected ranges. This does not adequately account for the importance of large cases. For example, if there were a problem affecting a very small number of very large records it would probably not be detected immediately.

n Recommendations

l Using SAS datasets that are created monthly from the BR perform a routine macro-level review. This review will compare the current months BR to the prior months and analyze changes and trends. This will allow us to see gradual changes in quality, for example an increase in the number of records not classified by industry that might not be seen in the quality assurance review. It also provides another level of review to assure the quality of the BR and identify any systematic errors that were not identified during processing.

l Creation of a Centralized Administrative Record Tracking System – This will allow staff BR processing staff, users, and managers information on all process activities associated with loading and quality assurance of source files. Two specific groups are targeted to use this software; employees of branches responsible for quality assurance of administrative records and managers from outside the production flow. The tracking system will serve as a central repository for all quality assurance documents (reports, tables, charts, etc.).

l Standardization and Automation of all Current QA Reports – Currently, staff keep detailed accounts of quality assurance activities. However, many of these activities take place manually (either via the filling out of a paper form or compiling a list in an Excel® Spreadsheet). The development of automated reports and statistical benchmarks (including the development of metrics to reject partial or complete source files) must be attained to enable QA personnel to identify anomalies more readily. This would also allow staff to perform higher quality statistical testing (such as trend or time series analysis) leading them to analyze data more effectively.

l Increase Ability to Identify Important Companies with Missing or Inaccurate Administrative Records - Current batch quality assurance procedures are adequate at identifying problems involving the total number of records in a single source file batch. However, a small number of records reporting for large individual companies can account for most of the receipts, payroll, and / or inventories in a given survey universe or sampling frame. We need to develop a more effective system to identify when these “big” records are missing from the administrative record loads or have other problems.

l Development of Systematic Review of Post-Processing Administrative Record QA –Develop methodology and standards for reviewing edit rejection and referral cases that affect the overall quality of the Business Register. Currently this review is dependent on the expertise of the analyst.

l Monitor Cost of Current Administrative Record Quality Assurance Activities - We need to develop accurate cost information on our quality assurance/control processes so that we can make decisions on how to allocate scarce resources. Costs may be measured in dollars, staff, computer time, or other resources.

3.3 Census Bureau Collections

The Census Bureau routinely applies quality assurance procedures to data collection and processing for the Company Organization Survey (COS), the economic censuses, and other economic surveys. For straightforward operations like data entry, these procedures include independent verification of samples drawn from work lots. Sampled records are re-keyed by a second person and differences are adjudicated by a third person. Decisions to accept or reject (rework) those lots are based on error rates estimated from the samples.

Batch processes that update the BR based on census and survey feedback also monitor those updates and enforce data integrity rules. Each variable is examined for validity and consistency using validity checks and ratio edits comparable to those described above for administrative records.

For clerical operations, quality assurance procedures monitor work samples for acceptability and provide feedback needed to improve staff skills and resolve process errors. Quality Control and acceptance procedures applied to clerical problem-solving work such as processing acquisitions, births, etc. reported by a company generally consist of the steps outlined below:

Ø A second person that is qualified as a verifier selects and inspects a sample of the referrals from each completed work unit (dependent verification); sampling rates generally vary according to the original production clerk’s qualification status and the size of the work unit. The verifier notes as defects all actions that do not comply with resolution procedures.

Ø The verifier classifies defects by type.

Ø The verifier corrects all defects.

Ø After completing inspection of the sample, the verifier counts the number of defects in the work unit (also may summarize defects by type classification).

Ø The verifier makes an accept/reject decision for the work unit based on the number/rate of defects compared to an acceptance criterion that is set to enforce a quality standard—e.g., at least 95% of flags resolved correctly (i.e., according to procedures).

Ø The verifier follows procedures for work unit disposition: any rejected work unit is reworked and subjected to 100% re-inspection/re-verification.

Previously, the interactive application that supported clerical problem solving for the old SSEL had specific functionality that supported clerical quality control. In particular, the application held updates for clerical work units until quality control was completed. Only the corrections for accepted work units were applied; corrections for rejected work units were discarded. Because of development workload and timing constraints, it was not possible to provide this kind of quality control functionality for the new BR and associated problem-solving applications implemented for the 2002 Economic Census. Instead, we relied on clerks who reworked and 100% verified rejected work units to detect and undo erroneous updates from the original production clerk’s work. This is one area were we are concerned that the lack of time to design and build the quality control software for the new BR might have resulted in a loss of quality. We are currently reviewing the existing process and requirements for quality control of these clerical operations and considering what software functionality is needed.

Additionally, data from Census Bureau collections are subjected to a variety of micro data edits and macrodata analysis designed to detect and resolve reporting errors as the information is prepared for use in statistical products. Editing and analysis for the annual County Business Patterns series are particularly important in this regard, as this statistical product presents tabulations of BR data, and the program’s data corrections are incorporated directly.

Because they play a uniquely important role in maintaining BR coverage for multi-establishment enterprises, the Company Organization Survey and the multiunit segment of the economic censuses incorporate specialized “completeness and coverage” edits. These edits evaluate data for each enterprise as a whole, for each affiliated EIN entity, and for each owned/operated establishment in order to identify extreme variation as compared to administrative (tax) data for the current period and to corresponding COS or census data for prior periods. The aim is to identify coverage errors, such as omissions and duplications, as well as more routine errors in reporting of establishments’ employment and payroll. Apparent problems are referred to a staff of COS specialists who use BR interactive applications and other resources to investigate discrepancies and correct errors.

3.4 Additional Recommendations / Areas of Investigation for Improving BR Quality

Ø Improve Error Tracking - Develop a system using Remedy Software to record and track errors. Users will be required to report errors using the Remedy Software. Error reports will be sent via Email automatically to staff responsible for responding. When solved, every error report will have a notation identifying the resolution. This will add accountability for error resolution and improve the Business Register by providing an electronic record of problem reports and their solution. Examination of the problem reports might also uncover systematic problems that can be corrected.

Ø Improve Imputation for missing Employment and Payroll Values – Currently imputation for missing values is generally done using either simple ratios applied to the prior period value or to correlated items, for example a missing employment value would be imputed by applying an expected current to prior ratio value for the industry. A study is underway to see if application of time series techniques to identify trends in individual establishments can be used to improve imputation.

Ø Evaluate ORACLE DQI (Data Quality Inspector) as way to identify problems - DQI is an ORACLE product that provides for storing groups of Oracle PL/SQL programs associated with executing specific user data quality tasks. Each task produces tables of potential problem records that can be reviewed. An initial pilot of DQI is being set up. Approximately ten business rules (for example every Enterprise identified as a multiple establishment company must be linked to at least two establishments) will be identified for inclusion with the pilot.

Ø Expand use of SAS datasets built from the BR to assess quality –The Business Register is a transactional Oracle database consisting of normalized tables that are designed for efficient loading and extraction of data. Relationships between records in these tables are not always obvious. Putting the different tables of a given universe and the different universes together in SAS data sets eliminates a major hurtle to starting any investigation of either the characteristics or quality problems of the Business Register. At the time a monthly SAS data set is created, a comparison is made between the current and previous month. This is a check on the quality of the created SAS data sets and a measure of change. This tells us the number of adds and drops from the BR, the number of variables that have changed from one month to another, etc. We are in the process of creating measures of change in records, variables, or the value of variables that can be used to compare on a monthly basis.

Ø Review and documentation of user needs and how the BR meets those needs – Many areas within the Census Bureau use the BR to select samples. These areas frequently have their own systems to assess the quality and integrity of the register for their use. This process will document those systems and results and hopefully provide further insight into the quality of the BR and processes to assure quality. In addition, anecdotal comments provided by users are being assembled for a comprehensive review.

Ø Comparison to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Business Establishment List (BEL)- Recent legislature was passed that allows the Census Bureau and BLS to share additional data for statistical purposes. Plans are underway to compare information the Census Bureau’s BR and BLS’s BEL. However, this comparison must still be limited due to restrictions on sharing of IRS Federal Tax Information.

4.0 Conclusion

Our analysis has found no identifiable difference in the quality of the new BR as compared to the old SSEL. Most of the quality tools and procedures remain the same with the migration. One area of concern is the lack of software and clearly defined procedures to support quality assurance of clerical processing. We have uncovered no evidence of deterioration in the quality of these procedures probably attributable to a very experienced staff that were able to provide training, quality assurance, and oversight for clerical procedures. We are beginning an analysis of these operations.

The team formed to develop a comprehensive quality plan has outlined several recommendations to improve BR quality and work is underway to evaluate and/or implement these recommendations. Overall many of the recommendations would move our operations from a dependency on the expertise of few individuals to a system that depends more on well-defined processes, standards, and controls; clearly a worthwhile goal.

Reference List

Walker, Edward (1997) “The Census Bureau’s Business Register: Basic Features and Quality Issues.” Presented at the Joint Statistical Meetings, Anaheim, CA

Comisarow, C.; Conley, D.; Fowler, J.; Hanczaryk, P.; Italiano, M.; Kornbau, M. and Moore, R.; “Economic Directorate Administrative Records Their Production Path and Quality Assurance.” (2004); Internal Census Bureau Document

Chapman, D. et al (2004), “Project Charter, Quality Assurance of the Business Register”; Internal Census Bureau Document

Chapman, D. et al (2004), “Comparison of SSEL and Business Register”; Internal Census Bureau Document